Manhattanville Transforms

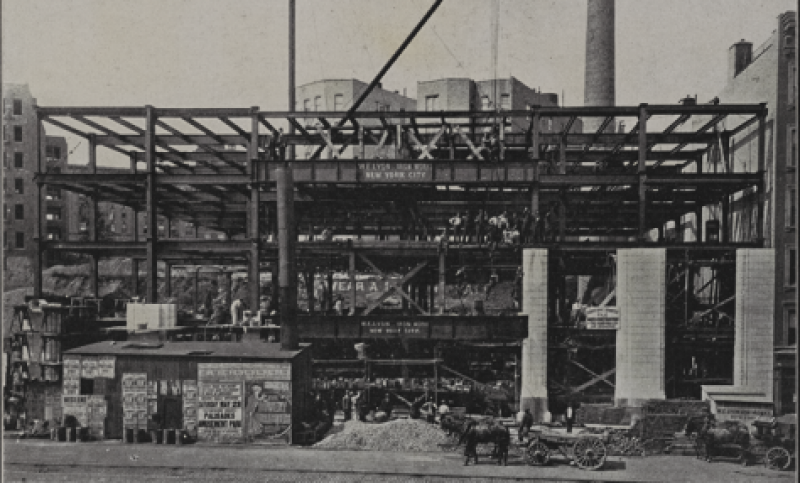

Within a block of its processing plant, Sheffield Farms constructed a multistory stable building on Broadway between 129th and 130th streets to house its delivery horses. At one point the company owned more than 1,000 horses (about half the number of humans it employed) to pull its wagons. The Manhattanville stable could accommodate more than 100 animals, as well as the wagons themselves.

For one hundred years, roughly from 1840 until 1940, the sharp clapping of iron horseshoes on stone that announced the approach of the milk cart was a familiar predawn sound for New Yorkers. During the industry’s heyday, in the Roaring 1920s, nearly six thousand wagons circulated throughout the city’s streets delivering milk to groceries, wholesalers, and individual consumers. Long after mechanized transport had transformed other industries, milk delivery remained animal-powered. But it couldn’t last. “Milk horses are doomed,” a headline in the New York Times proclaimed in 1938. By the end of that year Sheffield Farms planned to replace all its horses with trucks. Other companies were following the trend, the Times reported, and “within a short time horse and wagon milk deliveries in New York will be only a memory.”

In the age before refrigerated trucks and supermarkets, an entire infrastructure was dedicated to conveying dairy products from the farm to the consumer. During the 1920s, a quarter of a million New Yorkers were employed in this complex and necessary task. Each night, 32 trains were needed to offload milk at 11 terminals across the five boroughs of the city. Cows from more than 30,000 individual dairies – some from as far as 450 miles away – produced the milk to feed New York City. The station at 130th Street was among the busiest and largest in the city with between 26 to 30 employees and the capacity to offload 40 railcars of milk at any one time.

Milk was shipped in waist-high 40-quart cans, with about 300 fitting into each railcar. Ice was packed on top of the cans and on the ends of the cars to keep the liquid cool. Once the trains offloaded at Manhattanville, the raw milk was then pasteurized and bottled in the city. Milk that arrived by train at 130th Street at 11 pm would be at the Sheffield Farms plant by midnight and ready for the delivery wagon by two in the morning. The system lasted until after World War II. By then, refrigerated trucks had been built to carry the milk across the George Washington Bridge. It was no longer necessary to process the product in the city itself. In 1942, Sheffield Farms sold the stable building, which later housed plumbing, moving, and storage companies, most recently, Hudson Moving and Storage. The Jerome L. Greene Science Center is now located at this site. The processing facility was purchased by Columbia University in 1949 and renamed Prentis Hall.