The Problem with Milk

Considered by many to be the most life-giving of foods – especially for infants and children – milk, by the late-nineteenth century, had been transformed into a killer; a deadly and surprising result of progress.

Cows occupied New York ever since European colonists arrived. As long as the community clustered loosely around lower Manhattan and Brooklyn there had been no problem with local dairies providing fresh milk to the city’s children. But as the area of settlement expanded to become a teeming metropolis, real estate values climbed, and dairies removed further and further from their customers. By 1841, more than 300,000 residents lived in Manhattan, and most of the city’s milk was being imported from Long Island or New Jersey. That year Thompson Decker established a milk delivery route from his rural farm in the Bronx to the Lower East Side. His one-horse business eventually grew to become the Sheffield Farms company. The first trainload of “country milk” arrived in the city that same year, signaling a major trend to come.

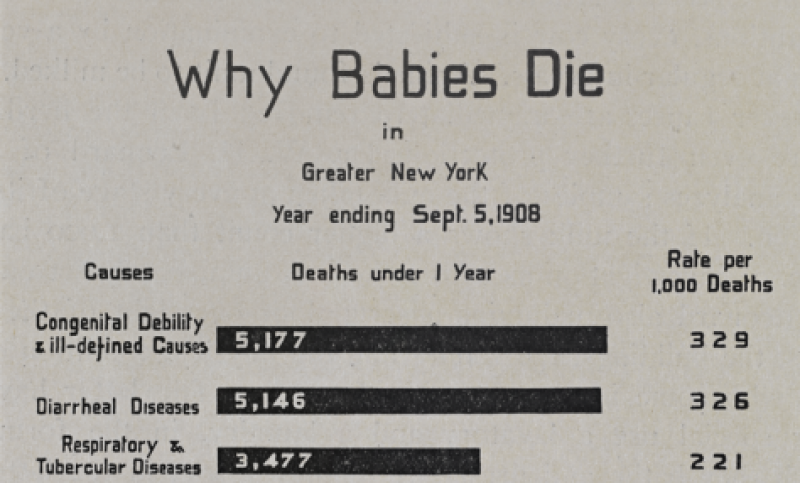

“Country milk” costing 15 cents per quart could only be afforded by the wealthy. Most families with young children purchased “loose milk” ladled out of open vats in putrid groceries for 4 cents per quart. Supplied by city cows, often fed on industrial waste, this “swill milk” — tinted a sickly blue, lumpy with chunks of dirt — was swarming with deadly bacteria that could cause tuberculosis, cholera, and a range of digestive ailments. In the 1840s, half of all children in New York died before reaching the age of five – and milk-borne disease was a prime cause.

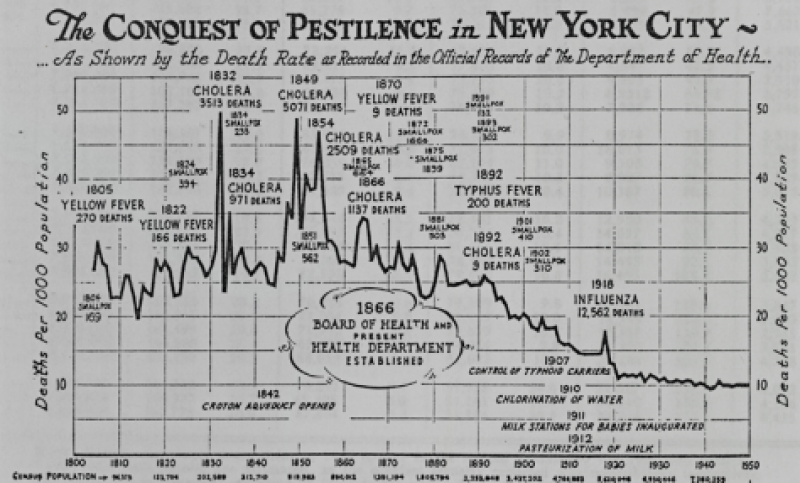

It took years for scientists to realize that milk was actually the culprit behind this fatal scourge. Beginning in the 1860s, Charles F. Chandler, a chemistry professor at Columbia University, took an active role investigating urban diseases. Chandler worked with the Board of Health to ban the sale of swill milk and began regulating milk markets in the 1870s, but a lack of expertise – and producers’ desire for profits – made it difficult to improve conditions.

By the 1880s, all of New York’s milk arrived by railroad. Often, a can of milk would travel 500 miles before reaching its destination. While this was a technological marvel, it did not solve the crisis. Containers sat on railroad cars in the sun. Delays in transit could lead to spoiling. By the time it reached consumers, it was “stale, dirty, and bacteria-laden.” Ironically, milk became increasingly more dangerous the more it embraced the modern age. As a result, infant-mortality rates were twice as high in the city than in the country.

Each summer, contaminated milk exposed to high temperatures created an epidemic of diseases. Milk-borne ailments could strike children of the rich, but it was the poorest residents of the city, surviving in crowded tenement houses who suffered most. New York City entered the twentieth century as a recognizably modern metropolis, complete with movie theaters, subways, and traffic jams. And yet from 1901 to 1905, nearly two in every ten children died before the age of one – a rate far worse than exists today even in the most destabilized or under-developed nations. This was an acute health crisis as well as a national disgrace – and the people of the city determined to take action to preserve their youngest and most vulnerable neighbors.